"I used to think I was the strangest person in the world

but then I thought, there are so many people in the world, there must be someone just like me who feels bizarre and flawed in the same ways I do

I would imagine her, and imagine that she must be out there thinking of me too.

well, I hope that if you are out there you read this and know that yes, it’s true I’m here,

and I’m just as strange as you."

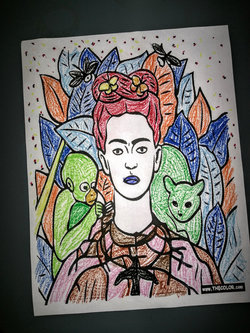

First of all, though widely attributed to Kahlo, it appears there is no proof she ever actually said it. There doesn’t even to seem to be a plausible suggestion that it was her. So why does everyone think she said it?

With a little digging, I learned that In 2008, a Canadian writer and artist named Rebecca Katherine Martin, just 15 at the time, mailed a postcard to the wildly popular blog PostSecret, a site that anonymously posts reader-submitted “secrets.” The idea is that, by posting the secret, it loses some of its power and the poster becomes somehow less alone. The postcard she created featured a partial picture of Kahlo, which seems to be the only reference to her.

Maybe there’s something to our desire to believe that a famous, beautiful artist felt as flawed and lonely as we do. Maybe that’s why the quote is consistently attributed to Kahlo. Or maybe it’s our inability to pay attention to a Google search longer than the first few results to figure it out. Maybe it’s both.

One of the places that the alleged Frida Kahlo quote surfaced this week was in a video I watched introducing the Mothers of Preschoolers theme for the year, and I could tell it resonated with my friends too. I lead our local MOPS group this year. You know, the group with the ridiculous name that I never wanted to join because I feared they might try to make me decorate a cake and talk about my feelings? Well, they've never made me decorate a cake. But MOPS has been a lot of beautiful things to me: a place to take my kids when the days felt long, friends and strangers to cook my dinners on nights when I couldn’t because I had just had a baby (or had just lost one), conversation in a place where I had neither friend nor family. But most of all, it’s made me feel less alone.

It goes like this:

“I drive a minivan.”

Me too.

“I miss reading fiction.”

Me too.

“I’m a Navy wife.”

Me too.

“I used to be a (fill in the blank), but now I’m not sure what’s next for me.”

Me too.

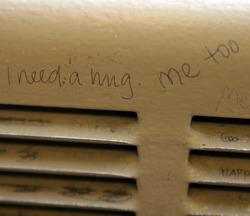

No one’s problems got solved after we did this. But I felt a buzz in the room. Because maybe that’s the thing I love most about MOPS; maybe that’s the reason I stay. Because of all the times I’ve walked in, shoulders slumped, worn down from the inherently lonely, mundane parts of motherhood. I’ve sat down with my coffee and started listening and something brightened as I heard myself say, “me too.”

This week has been so heavy. Two more police shootings of black men, days and nights of sometimes violent protest in Charlotte, renewed fighting in Syria, continued vitriol on the campaign trail. And as a result, I see my circles, my acquaintances, my newsfeed fearful, angry and divided.

Where we live, it’s also been a week of rain. School was closed for two days because of the flooding and, despite the bickering and boredom, I was grateful to hold my babies close.

They learned this week that little friends of theirs had lost their mother just last month. What they don’t know is that it was suicide that took her. These precious children's beautiful mother, whom I didn’t really know, was so overcome— with her illness, her problems, her flaws—that the end seemed a gift. Finding out stole the breath from my lungs. While we must protect the innocence of our children and hers, I don’t think we can whitewash this. Did she have a place where she could hear another say, “Me too?” I have to believe her people did all they could to save her. But did she have the help she needed? Would she have accepted it? Would it have made a difference?

I certainly don’t know, and no part of me is trying to simplify what is never simple and can never be fixed from the outside in. But I know just enough about the darkness within me to know that it's a liar, and that total retreat is not an option.

What would happen if we didn’t hide our brokenness? If we wore it, not as a badge of honor, but as a reminder of our humanity, of our connectedness to everyone else? As a Christian I believe that nothing separates me from anyone else, or from the depravity and death and darkness of this world but for the grace of God and His son, my savior, Jesus Christ, who can pull anyone, anyone, ANYONE out of the depths. If I really believe that, to my bones, I don’t need insulation or separation or protection from anyone else’s broken pieces; they can only cut me so deep. This knowledge should compel me into the dark places with compassion, with understanding, with an arm ready to wrap around hunched shoulders, the gentle words, “me too,” on my lips.

May we all seek out a place to rest, where we can bring our pain and flaws and mistakes and strangeness and lay it bare. Not just online--where it's so easy to posture, to project, to cover up and to hide--but in real life. Where sisters and brothers would look at us tenderly and say, “Me too,” and refuse to let us leave the way we came in. May we not believe the lie that these sisters and brothers need to look just like us, talk just like us, tell all the same stories and live just like us in order to be the people for us. And if you can't find that place, maybe you can make it yourself. Being vulnerable will not keep you safe, but it also won't allow you to stay lonely. And it might just make it safe for others to come out of hiding and say, "Me too."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed